Anne Elise Crafton is a Ph.D. candidate at the Medieval Institute at the University of Notre Dame. She is a scholar of Old English and her dissertation focuses on women's speech in the extant vernacular texts. During the winter break of the 2023-24 academic year, she traveled to Rome with funding from both the Nanovic Institute for European Studies and the Medieval Institute at Notre Dame to join the Notre Dame Rome Global Gateway’s intensive course on studying manuscripts and completed her own research.

When the opportunity arose to travel to Rome, Italy, for an intensive course on the study of medieval manuscripts, my interest was piqued. When I learned that, as part of this course, I would spend time reading unique manuscripts in the exclusive Vatican Library (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana), I knew I could not miss this chance.

Every two years, the University of Notre Dame’s Rome Global Gateway hosts an intensive two-week course on the study of Latin paleography (the study of handwriting) and codicology (the study of manuscripts), which includes four days in the Vatican Library and formal presentations of research to fellow students. Aside from the numerous intellectual benefits of the program, we also had the benefit of staying near the Colosseum itself.

Training to read manuscripts at the Vatican Library

The program is internationally competitive — we had two students from Belgium, four from Italy, one from France, and five from the United States — and rigorous. Each day, we spent between 10-12 hours at the Rome Global Gateway, staring intently at images of manuscripts as we attempted to read the centuries-old scrawl. The first week was both exhausting and incredibly rewarding, as we quickly transformed from inexperienced beginners to practiced experts. This rapid expertise was needed because, in addition to a week of intensive study, we also spent a week in practical research at the Vatican Library.

The Vatican Library (BAV) is a public, if restricted, collection of medieval and modern manuscripts. The library dates from the fifteenth century and houses over 80,000 manuscript items, many of which contain wholly unique examples of their contents. Though the library is open to the public, access to the collections requires formal letters of introduction and documentation. Once granted entry, however, a Vatican library pass, if consistently renewed, is valid for life. Each student in our program was assigned a manuscript relating to their research to analyze and describe in full; some were assigned weighty tomes bigger than a toddler, while others, including me, had minuscule fragments of lost compilations. The manuscripts examined represented the vast variety of materials that survived from the medieval era: from paper to parchment, from the 11th to 15th centuries, and from elaborately illuminated to scribbled marginalia.

Practical study yields new insights

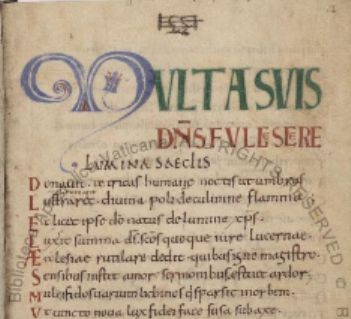

I was assigned Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Reg. lat. 204, an 11th-century copy of Bede’s metrical uita Cuðberhti. The small, 24-folio manuscript had once been a part of a larger compilation, likely composed at a scriptorium in Canterbury, England (perhaps St. Augustine’s or Christ Church) in the early 11th century. Little is known of its use and existence until the 13th or 14th centuries, when it came into the library of the Abbaye St-Florentin et St-Hilaire in Bonneval, France. The monastery was destroyed by a Protestant mob in the late 16th century, at which point the manuscript came into the hands of noted book collector Paul Pétau of Orlean. Paul’s son Alexander sold much of his father’s collection to Queen Christina of Sweden, who then, in turn, donated her vast collection to the Vatican Library in the 17th century. For such a small and seemingly uninteresting manuscript, it has a rich history. Each owner left a mark on the manuscript: the Bonneval abbey claimed ownership in a careful cursive script, the shelfmarks and marginal notes of Paul and Alexander are still visible on the first two folia, and the shelfmark of Queen Christina still sits above the opening of the uita in a thick, black crayon.

I was initially interested in this manuscript merely for its date and region of origin – there are few pre-Conquest English manuscripts in the Vatican collection. Rarer still, the manuscript contains 13 glosses of the Latin uita in Old English. Yet, through careful research and a close examination of both the paleography and construction of the manuscript (using the very skills I learned the previous week), I was able to identify several fascinating characteristics. First, the manuscript is of a low production value. Compared to several contemporary versions of the same text produced by the same scriptorium:

-

The folia of Reg. lat. 204 are comprised of scrap parchment, at times sloppily glued together to create full bifolia.

-

Each quire (group of pages) was constructed, ruled, rubricated, and written noticeably differently.

-

The decoration is limited to alternating colors instead of the more elaborate (and more typical) zoomorphic initials.

-

Each of the manuscript’s four hands is distinct in its varying execution of the script known as “Anglo-Caroline minuscule.”

There is still much to explore, but for now, I can confidently say that Reg. lat. 204 promises to tell us much about book production and variability in scribal hands in 11th-century Canterbury. I am incredibly grateful to the Nanovic Institute and the Medieval Institute, which were willing to fund my trip to Rome, for enabling not only training critical to my career but also an exciting new research avenue.

Read more stories on Nanovic Navigator